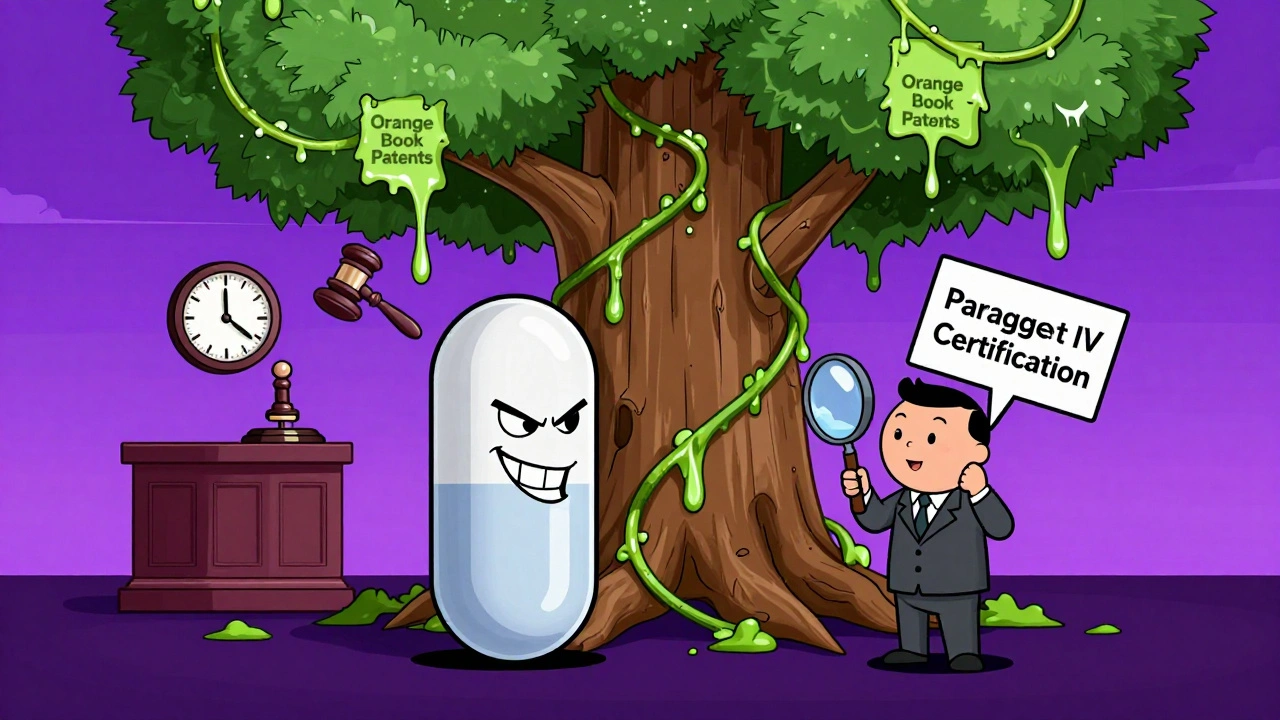

When a generic drug company wants to sell a cheaper version of a brand-name medicine before the patent runs out, it can’t just copy the pill and start selling. There’s a legal trapdoor built into U.S. drug law - called a Paragraph IV certification - that lets them challenge the patent head-on. It’s not a loophole. It’s a deliberate, high-stakes legal mechanism created by Congress in 1984 to balance innovation with access. And it’s how most generic drugs enter the market early.

What Exactly Is a Paragraph IV Certification?

A Paragraph IV certification is a formal statement included in an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) filed with the FDA. It says: "This generic drug won’t infringe your patent, or your patent is invalid or unenforceable." That’s it. No fancy language. Just a legal declaration that directly challenges the brand’s patent rights.

This isn’t just a filing. It’s an act of legal provocation. Under the Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984, this single statement triggers what courts call an "artificial act of infringement." That means even though the generic drug hasn’t been made or sold yet, the patent holder can sue. The system forces patent disputes into court before the generic hits the shelves. That’s the whole point - avoid chaos in the marketplace later.

It’s not optional. If you’re filing an ANDA and there’s a patent listed in the FDA’s Orange Book for the brand drug, you have to pick one of four certification types. Paragraph IV is the only one that challenges the patent. The others are either passive ("patent expired") or deferential ("we’ll wait until patent expires"). Only Paragraph IV opens the door to early entry - and big rewards.

Why Do Companies Risk It?

The risk is huge. A Paragraph IV challenge can cost $10 million to $15 million in legal fees. The lawsuit can drag on for years. If the brand wins, the generic gets blocked from the market for 30 months - and pays damages. But if the generic wins? They get 180 days of exclusive rights to sell the generic version with no competition.

That exclusivity period is worth millions - sometimes hundreds of millions. Take Mylan’s challenge to Gilead’s hepatitis C drug Viread. Mylan won, and entered the market 27 months before the patent expired. During its 180-day exclusivity window, it captured nearly the entire market. That’s not just profit - it’s market dominance.

That’s why 60% to 70% of all ANDAs filed today include a Paragraph IV certification. For big-selling drugs - those making over $1 billion a year - it’s almost guaranteed someone will file one. The economic incentive is too strong to ignore. Since 1984, these challenges have saved U.S. consumers over $1.7 trillion in drug costs.

The Four Types of Patent Certifications

There are four paths a generic company can take when filing an ANDA. Only one leads to a patent fight.

- Paragraph I: "This drug isn’t patented." Used in about 5% of cases. Low risk, no reward. Just a formality.

- Paragraph II: "The patent expired." Used in 15% of cases. Simple. Safe. No lawsuit. You can launch as soon as the patent ends.

- Paragraph III: "We’ll wait until the patent expires." Used in 20% of cases. Companies that don’t want to fight. They get approval, but no early entry.

- Paragraph IV: "Your patent is invalid or won’t be infringed." Used in 60-70% of cases. High risk. High reward. This is where the real action happens.

Paragraph IV is the only one that forces a court battle. It’s also the only one that gives you a shot at 180 days of exclusivity. That’s why it’s the most common - and the most complicated.

How the Process Actually Works

It’s not just about filing a form. It’s a legal chess game with strict rules.

- File the ANDA with Paragraph IV certification. The FDA doesn’t approve the drug yet - it just accepts the application.

- Send a notice letter to the brand company within 20 days. This letter must include a "detailed statement" explaining why the patent is invalid or won’t be infringed. Vague language? Your application gets rejected. The FDA requires a rational, factual basis - not just a legal opinion.

- Wait for the lawsuit. The brand has 45 days to sue. In 92% of cases, they do. If they don’t, the generic can launch immediately.

- Trigger the 30-month stay. Once the lawsuit is filed, the FDA can’t approve the generic for 30 months - unless the court rules in the generic’s favor sooner.

- Win or lose in court. If the generic wins, they get approval and 180 days of exclusivity. If they lose, they wait until the patent expires.

That 30-month stay is critical. It’s not a guarantee - courts can shorten it if the generic is dragging its feet or extend it if the brand files new patents. But for most cases, it’s the clock that ticks until the legal battle ends.

The Big Risk: Losing Your 180-Day Exclusivity

Getting the 180-day exclusivity isn’t automatic. You have to be the first to file a substantially complete ANDA with a Paragraph IV certification. And you have to actually market the drug.

That’s where companies mess up. Teva filed a Paragraph IV challenge for Copaxone in 2014. They won the case. But they didn’t get tentative approval within 30 months. The FDA approved their drug - but because they missed the deadline, they lost their exclusivity. Five other generics launched the same day. Teva’s market share collapsed.

Other ways to lose exclusivity:

- Withdrawing your ANDA after filing

- Changing your Paragraph IV certification to a Paragraph III

- Getting sued by a different patent holder after filing

- Failure to market within 75 days of approval

One misstep - and you’re back to competing with everyone else.

Pay-for-Delay and the FTC’s Fight

Not every Paragraph IV challenge ends in court. Sometimes, the brand and generic settle - and the brand pays the generic to stay off the market. That’s called a "pay-for-delay" deal.

The FTC calls it anticompetitive. Between 1999 and 2009, they documented 197 of these deals. In one case, a brand paid a generic $100 million to delay its launch for five years. The Supreme Court ruled in 2013 (FTC v. Actavis) that these deals aren’t automatically legal. They can be challenged under antitrust law.

Since then, pay-for-delay deals have dropped - but they haven’t disappeared. The FTC still investigates them. And now, brand companies are using "authorized generics" - launching their own generic version during the 180-day window - to undercut the first filer. The FTC challenged this in 2021 (FTC v. Shire), saying it’s another way to block competition.

What’s Changing in 2025?

Patent thickets - piles of overlapping patents on the same drug - used to make Paragraph IV challenges nearly impossible. A brand would file 10 patents on minor changes: coating, dosage, delivery method. Generic companies had to challenge them all.

The FDA’s 2023 Orange Book Modernization Act changed that. Now, only patents that truly cover the drug’s active ingredient or approved use can be listed. That’s cutting down the noise.

Another shift: more generic companies are combining Paragraph IV challenges with Inter Partes Review (IPR) at the Patent Trial and Appeal Board. IPR is cheaper and faster than district court. In 2023, 42% of Paragraph IV cases included parallel IPR filings. That’s a new strategy - attack the patent on two fronts.

But there’s a new hurdle. The Supreme Court’s 2023 decision in Amgen v. Sanofi raised the bar for patent invalidity. Now, a patent must enable the full scope of its claims - not just a few examples. That’s making it harder to challenge biologics and complex drugs.

Who’s Winning? The Big Players

The Paragraph IV game is dominated by five companies: Teva, Viatris, Sandoz, Hikma, and Amneal. Together, they filed 58% of all Paragraph IV certifications in 2022-2023. They have legal teams, patent analysts, and in-house scientists who track patents years in advance.

Smaller generics still play - but they need to be smart. They target drugs with weak patents or where the brand has a history of losing in court. Apotex beat GlaxoSmithKline on Paxil in 2004 and made over $1.2 billion during its exclusivity window. That’s the dream.

But the reality? Most challenges fail. The median cost is $12.7 million. The average case takes 4 to 5 years. And the brand usually has deeper pockets.

Is It Still Worth It?

For a drug making $2 billion a year, a $500 million payday during 180 days of exclusivity makes the risk worth it. That’s why 90% of top-selling brand drugs face at least one Paragraph IV challenge.

It’s not just about money. It’s about access. Without Paragraph IV, generics would wait until patents expire - sometimes years after they could be made. Patients would pay more. Insurance companies would spend more. The system works because it forces innovation to compete - not just hide behind patents.

It’s messy. It’s expensive. It’s litigious. But it’s also the reason you can buy a generic version of Lipitor for $4 instead of $300. That’s the real value of Paragraph IV.

What Happens If You Get It Wrong?

One mistake can cost you everything. A poorly written notice letter? FDA rejection. Missing the 20-day deadline? Application thrown out. Failing to market within 75 days of approval? Exclusivity gone.

Companies that win are meticulous. They hire patent attorneys who specialize in Hatch-Waxman law. They spend months drafting the detailed statement - not just copying legal jargon. They test their arguments with mock trials. They know the FDA and courts care about substance, not style.

As one industry insider put it: "Winning a Paragraph IV case isn’t about being right in court. It’s about being right on paper before you even file."

so like... paragraph iv is basically the drug world’s version of ‘i dare you’? 😅

wait so they just file this thing and then wait for the big pharma to sue them?? like… that’s wild. i thought the law was supposed to protect people, not turn drug pricing into a courtroom thriller.

so the system rewards the company that can afford to lose $15 million… just to win the right to make $500 million? classic capitalism. i’m shocked.

it’s funny how we call this a ‘legal trapdoor’ like it’s some sneaky backdoor, but it’s literally written into law by congress. it’s not a loophole-it’s a feature. we built a system where the only way to make medicine affordable is to gamble millions on a legal Hail Mary. we’re not broken. we’re designed this way. and it works. because without it, you’d still be paying $300 for lipitor. you’re welcome.

the real tragedy isn’t the lawsuits. it’s that we’ve normalized this as the only path to fairness. imagine if innovation and access weren’t locked in a deathmatch. imagine if we just… paid for drugs differently. but no. we’d rather let lawyers decide who lives and who doesn’t. that’s the real paragraph iv.

and don’t get me started on pay-for-delay. that’s not capitalism. that’s collusion with a law degree. the FTC’s fighting it, but they’re outgunned. brand companies have more money than the entire FDA budget. and yet we act like this is just ‘business.’

the 180-day exclusivity? genius. it turns the underdog into a monopoly overnight. it’s like giving the first person to jump off a cliff a golden parachute. and then pretending the cliff wasn’t there in the first place.

and now they’re combining it with IPRs? smart. two fronts. the patent office and the courtroom. it’s like playing chess with a flamethrower. the system’s getting more complex, not more fair.

but here’s the quiet truth: most generics never make it. the cost, the time, the risk. it’s not a game for the small players. it’s a war fought by five companies with armies of patent lawyers. the rest of us? we just get the pills. and we’re supposed to be grateful.

so yes. paragraph iv saves lives. but it also turns medicine into a bloodsport. and we call it progress.

the irony is that this whole system exists to reduce costs… yet the legal fees alone could fund a national healthcare program. 🤔

and now we’re seeing brand companies launch their own generics to sabotage the first filer? brilliant. just brilliant. the market is a circus, and we’re all paying for tickets.

also, the amgen v. sanofi decision? that was a gift to big pharma. if you can’t invalidate a patent unless you can prove every possible version of the drug works, then good luck challenging biologics. goodbye, affordable insulin.

we’re not innovating. we’re just rearranging the deck chairs on the titanic.

ok but can we talk about how teva lost their exclusivity because they missed a deadline?? like… you won the court case, you did everything right… but one tiny paperwork error and suddenly you’re just another generic in the pile? that’s not justice. that’s a bureaucratic nightmare. and it’s happening to real people who need these drugs. i’m crying. 🥺

and then there’s the fact that these companies spend years and millions just to get a 6-month window to make bank? it’s insane. it’s like winning the lottery… but you had to survive a war to get the ticket.

the real heroes are the scientists who build these drugs. the lawyers? they’re just the ones who get to cash in. and the patients? they’re just trying to survive.

and yet… we still get cheaper meds. so i guess we win? even if the system is broken?

let me be clear: this is not just about drugs. this is about power. the patent system was never meant to be a weaponized monopoly engine. but here we are. big pharma holds the keys to life-saving medicine, and the only way to break their grip is to force them into court. that’s not innovation. that’s survival.

and the 180-day exclusivity? it’s a brilliant incentive-but it’s also a trap. you win, you get rich. you lose, you’re bankrupt. and the FDA? they’re just the referee who doesn’t know the rules anymore.

the orange book modernization? a step forward. but it’s not enough. we need to ban pay-for-delay. we need to cap legal fees. we need to stop letting patent thickets strangle competition.

and we need to stop pretending this is a market. it’s a battlefield. and the casualties? they’re the people who can’t afford their prescriptions.

so yes. paragraph iv saves lives. but it also exposes how broken our system is. and if we don’t fix it, someone else will have to fight it all over again. and i don’t want to be that person.

i just read this whole thing and now i’m emotionally drained. how is this legal? how is this normal? how are we okay with a system where the only way to get a cheap pill is to risk everything on a lawsuit? i’m not mad. i’m just… heartbroken.

paragraph iv certification is a strategic instrument under the hatch-waxman act designed to balance innovation incentives with public health imperatives. the 180-day exclusivity provides necessary market entry incentive. litigation risk is inherent in any patent challenge. the system functions as intended. compliance with procedural deadlines is mandatory. failure to market within 75 days of approval constitutes forfeiture of exclusivity rights. regulatory clarity has improved with orange book modernization. parallel ipr filings enhance efficiency. judicial standards remain consistent with statutory intent. the economic impact on consumers is demonstrably positive. the system is complex but functional.