Generic drugs make up 90% of all prescriptions filled in the U.S. today. That’s not luck. It’s the result of a 40-year-old law designed to break monopolies and bring down prices. But behind the scenes, big pharmaceutical companies have spent decades trying to block that competition - and the courts, regulators, and taxpayers are still cleaning up the mess.

How the Hatch-Waxman Act Was Supposed to Work

In 1984, Congress passed the Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act - better known as the Hatch-Waxman Act. It was a compromise. Branded drug makers got extra patent time to make up for delays in FDA approval. In return, generic companies got a faster, cheaper path to market. The key incentive? The first generic company to challenge a patent and win gets 180 days of exclusive rights to sell the generic version. No one else can enter during that window. That’s a huge reward - and it’s meant to encourage bold, risky lawsuits against overprotected patents.

Before Hatch-Waxman, only 19% of prescriptions were filled with generics. By 2016, that number jumped to 90%. Between 2005 and 2014, Americans saved $1.68 trillion on drugs because of generic competition. In 2012 alone, that savings hit $217 billion. That’s not a minor discount. That’s life-changing money for people paying for insulin, heart meds, or cancer treatments.

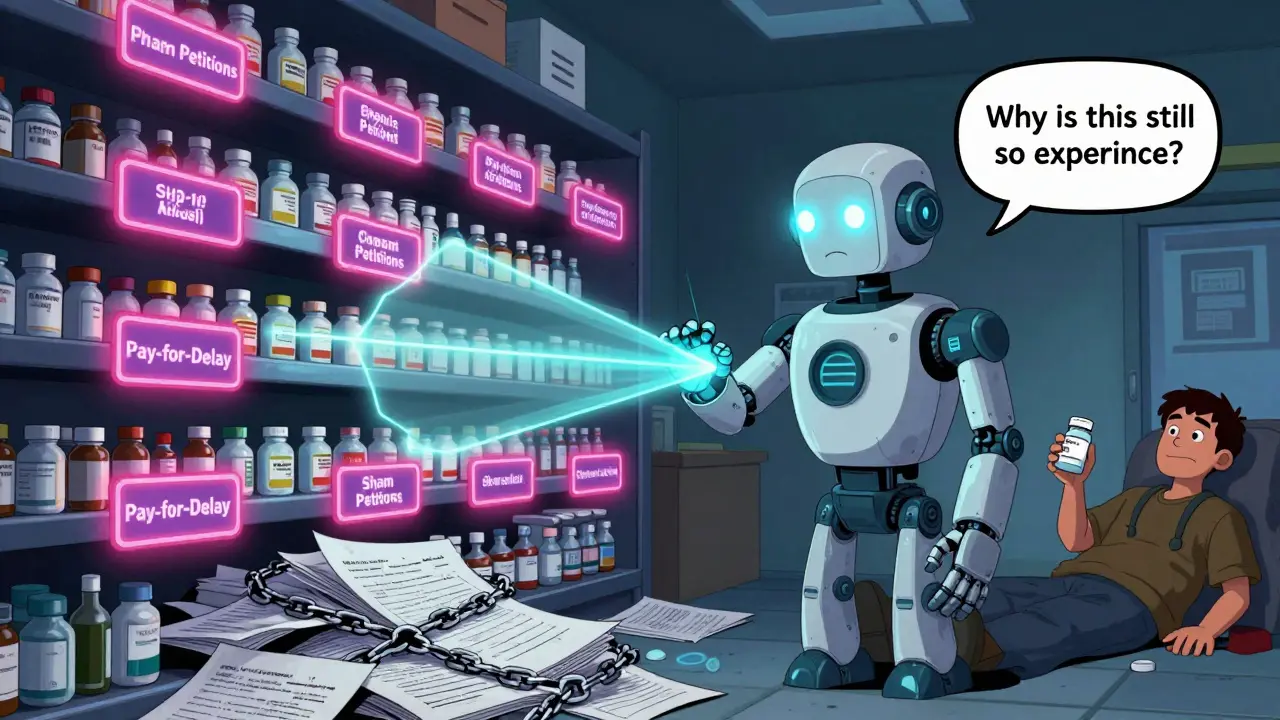

The Dark Side: Pay-for-Delay Schemes

But here’s the problem: instead of racing to be first, some generic companies started making deals with the brand-name makers. They’d agree to delay their entry - in exchange for cash. This is called a “pay-for-delay” agreement. The branded company pays the generic to stay off the market. No competition. No price drop. Just a quiet handshake that costs consumers billions.

The FTC has been fighting this since the early 2000s. In 2013, the Supreme Court ruled in FTC v. Actavis that these deals aren’t automatically legal just because they involve a patent. If the payment is large and unexplained, it’s likely an antitrust violation. That opened the door for lawsuits. In 2023, Gilead Sciences paid $246.8 million to settle allegations it paid generic makers to delay an HIV drug. Between 2000 and 2023, the FTC pursued 18 pay-for-delay cases. The total settlements? Over $1.2 billion.

These aren’t just legal technicalities. When a generic drug finally enters, prices drop by at least 20% in the first year. With five competitors, prices fall nearly 85%. But if a pay-for-delay deal holds off entry for even six months, patients pay thousands more in out-of-pocket costs. A 2022 Kaiser Family Foundation survey found 29% of U.S. adults skipped or cut back on meds because they couldn’t afford them. Many of those cases trace back to delayed generic access.

Other Tricks: Product Hopping, Sham Petitions, and Orange Book Abuse

Pay-for-delay isn’t the only trick. Another common tactic is “product hopping.” A company slightly changes its branded drug - maybe switches from a pill to a capsule, or adds a coating - right before the patent expires. Then it pushes doctors and patients to switch to the new version. The original drug? It gets pulled from the market. Suddenly, the generic version of the old drug is useless. No one can fill prescriptions for it. The new version? Still under patent. The generic makers are stuck.

AstraZeneca did this with Prilosec and Nexium. Courts eventually dismissed a monopolization claim because the company didn’t block generic entry - it just changed the product. But the FTC still calls it anti-competitive. And patients? They paid more for a drug that wasn’t meaningfully better.

Then there are “sham citizen petitions.” Companies file fake complaints with the FDA, claiming a generic drug is unsafe or poorly studied. These petitions aren’t meant to protect public health - they’re meant to delay approval. The FTC took action against Teva Pharmaceuticals in 2023 for filing these petitions to block a generic version of Copaxone, a multiple sclerosis drug. The case is still pending.

And don’t forget the Orange Book. That’s the FDA’s official list of patents for branded drugs. Generic companies must check this list before filing their applications. But some branded companies list patents that don’t even cover the drug’s active ingredient - or file patents after the drug is already on the market. In 2003, Bristol-Myers Squibb was fined for listing patents that had nothing to do with its drug’s formulation. The goal? To confuse generic makers and scare them away.

Global Comparisons: How Europe and China Are Handling It

The U.S. isn’t alone in this fight. The European Commission has opened 27 antitrust cases in the pharmaceutical sector between 2018 and 2022. Sixty percent of them focused on delaying generic entry. One tactic they’ve cracked down on? Withdrawing marketing authorizations in specific countries to block generic imports. Another? Spreading false claims about generics being less effective or unsafe. This is called “disparagement.”

China took a hardline approach in January 2025 with its new Antitrust Guidelines for the Pharmaceutical Sector. They identified five “hardcore restrictions” that are automatically illegal: price fixing, market division, output limits, joint boycotts, and blocking new technology. By Q1 2025, six cases had been penalized - five involved price fixing through messaging apps and algorithms. Chinese regulators are now using AI to track suspicious pricing patterns in real time.

Europe’s Commissioner Margrethe Vestager put a dollar figure on the damage: delayed generic entry costs European consumers €11.9 billion every year. That’s not a typo. That’s billions lost to corporate maneuvering.

Who Pays the Price?

When antitrust laws are ignored, it’s not just insurers or pharmacies that lose. It’s patients. A 2023 Congressional Budget Office report found generic competition reduces drug prices by 30% to 90%. That’s the difference between paying $300 a month or $30. For people on fixed incomes, that’s whether they eat, pay rent, or take their meds.

And it’s not just about cost. When generics are delayed, adherence drops. People skip doses. They go to the ER. They end up hospitalized. The ripple effect hits the whole system.

There’s also a psychological toll. Patients who’ve been told for years that generics are “just as good” feel betrayed when they find out the system was rigged to keep them expensive. Trust in the system erodes. And that’s harder to fix than any price tag.

What’s Next?

The FTC continues to push for stronger enforcement. Their 2022 workshop on generic drug entry after patent expiration highlighted new concerns: algorithm-driven price coordination, digital collusion through messaging platforms, and the rise of “biosimilars” - the next frontier in biologic drug competition.

But enforcement is slow. Lawsuits take years. Companies have deep pockets. And the legal gray areas - like product hopping or sham petitions - are still being tested in court.

What’s clear is this: the Hatch-Waxman Act worked. It delivered on its promise. But the system is under constant attack. Without strong, consistent antitrust enforcement, those 90% generic rates won’t last. The savings won’t continue. And patients will keep paying more than they should.

Competition isn’t just good economics. It’s a public health issue.

What is the Hatch-Waxman Act and how does it affect generic drugs?

The Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984 created a legal pathway for generic drug manufacturers to bring lower-cost versions of branded drugs to market. It allows generics to rely on the branded drug’s safety data, cutting approval time and cost. In exchange, the first generic company to successfully challenge a patent gets 180 days of exclusive market rights - a powerful incentive to take on expensive lawsuits. This law is why 90% of U.S. prescriptions are now filled with generics.

What are pay-for-delay agreements and why are they illegal?

Pay-for-delay agreements happen when a branded drug company pays a generic manufacturer to delay launching its cheaper version. These deals prevent competition, keeping prices high. The Supreme Court ruled in 2013 that such agreements can violate antitrust laws if they involve large, unexplained payments. The FTC has pursued over 18 such cases since 2000, with settlements totaling more than $1.2 billion.

How do pharmaceutical companies use the Orange Book to block generics?

The Orange Book lists patents associated with branded drugs. Generic companies must address each listed patent before entering the market. Some branded companies abuse this by listing patents that don’t actually cover the drug’s active ingredient - or by filing weak or late patents. This creates confusion and legal barriers, scaring off potential generic competitors. The FTC fined Bristol-Myers Squibb in 2003 for this exact tactic.

What is product hopping and is it illegal?

Product hopping is when a drug company makes a minor change to its branded drug - like switching from a pill to a capsule - right before its patent expires. Then it pushes doctors and patients to switch to the new version and pulls the old one from the market. This makes the existing generic version useless. While courts have sometimes dismissed claims because the branded drug wasn’t technically blocked, regulators like the FTC consider it anti-competitive behavior that harms consumers.

How does China regulate antitrust in generic drug markets?

China’s 2025 Antitrust Guidelines for the Pharmaceutical Sector identify five practices as automatically illegal: price fixing, market division, output restrictions, joint boycotts, and blocking new technology. As of early 2025, six cases had been penalized, five involving price fixing through messaging apps and algorithms. Chinese regulators now use AI to monitor pricing trends in real time, making collusion harder to hide.

Why do generic drug prices drop so much when they enter the market?

When the first generic enters, prices typically drop by at least 20% within a year. With five or more generic competitors, prices fall nearly 85%. That’s because generics don’t have to recoup billions in R&D costs. They copy an existing formula, so their production costs are low. Competition among multiple generic makers drives prices down further. This is why generic drugs save consumers hundreds of billions annually.