Pancreatitis Risk Calculator for GLP-1 Therapy

This tool assesses your patient's pancreatitis risk when considering GLP-1 receptor agonists based on key clinical factors. The absolute risk is generally low (<0.5%), but certain factors increase risk. Results will guide appropriate monitoring and alternative medication considerations.

Key Takeaways

- GLP‑1 receptor agonists (GLP‑1 RAs) lower blood sugar and aid weight loss, but they carry a debated pancreatitis risk.

- Current evidence is mixed: large real‑world studies show both a modest increase and no increase in acute pancreatitis.

- Baseline lipase/amylase testing and patient education on abdominal pain are the core monitoring steps.

- Patients with heavy alcohol use, high triglycerides, smoking, or chronic kidney disease need tighter follow‑up.

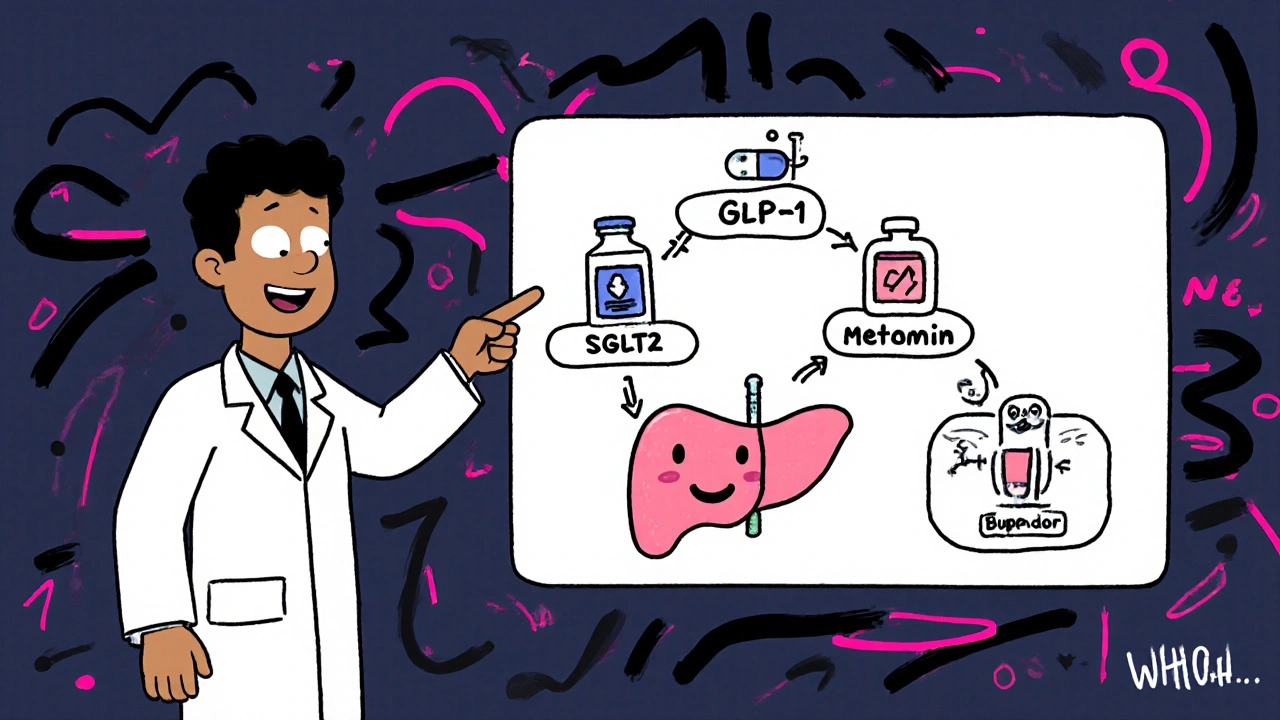

- When risk is a concern, SGLT2 inhibitors, metformin, or bupropion‑naltrexone provide effective alternatives with lower pancreatic danger.

What are GLP‑1 receptor agonists?

GLP-1 receptor agonists are a class of injectable medications that mimic the hormone glucagon‑like peptide‑1 (GLP‑1) to stimulate insulin, suppress glucagon, slow gastric emptying, and increase satiety. First approved in 2005 (exenatide), the group now includes liraglutide, semaglutide, and tirzepatide, all of which are used for type 2 diabetes and, increasingly, obesity management.

How GLP‑1 RAs could affect the pancreas

The drugs bind to GLP‑1 receptors on beta cells, boosting glucose‑dependent insulin release. They also act on alpha cells to lower glucagon. By delaying gastric emptying (30‑50% slower in scintigraphy studies) they raise intra‑ductal pressure, a theoretical trigger for pancreatic enzyme activation. Structural differences matter: exenatide is a 39‑amino‑acid peptide from Gila monster venom, while liraglutide and semaglutide are human analogs with fatty‑acid side chains that extend half‑life from minutes to weeks. Those modifications may alter how long the pancreas is exposed to receptor activation, but direct cause‑effect data are still lacking.

What the data say about pancreatitis risk

Research from the last three years paints a confusing picture.

- May 2025: A TriNetX analysis of 992,901 diabetics found a 34 % higher hazard of acute pancreatitis at six months (HR 1.34) and a 44 % rise in chronic pancreatitis over five years (HR 1.45) among GLP‑1 RA users.

- Feb 2025: A Journal of Clinical Medicine cohort (969,240 patients) reported no statistically significant difference in pancreatitis incidence between GLP‑1 RA users and non‑users at any time point; the absolute risk stayed below 0.4 %.

- Sept 2023 (JAMA): Compared GLP‑1 RAs with bupropion‑naltrexone and observed a nine‑fold higher adjusted hazard (HR 9.09), though the sample was under 5,000.

- Jan 2025 (J Diabetes Metab Disord): Suggested a dose‑dependent rise in pancreatitis, with larger cumulative doses correlating with higher events.

- Apr 2024 (ENDO conference): Showed GLP‑1 RAs may actually lower recurrence of acute pancreatitis versus SGLT2 inhibitors in a multinational dataset of 127 million patients.

Because the background rate of pancreatitis in diabetes is already elevated, extracting a causal signal is tough. Most regulatory agencies keep the warning but note that the absolute risk stays under 0.5 % in most real‑world populations.

Monitoring protocols you can put into practice

Guidelines from the American Diabetes Association (2024) and drug labels converge on three pillars: baseline labs, symptom vigilance, and targeted re‑testing.

- Baseline testing: draw serum lipase and amylase before starting therapy, especially if the patient has a prior pancreatitis episode.

- Patient education: teach patients to call you if they develop sudden, severe upper‑abdominal pain that radiates to the back, nausea/vomiting, or pain that worsens after meals.

- Follow‑up labs:

- High‑risk patients (history of hyper‑triglyceridemia >500 mg/dL, heavy alcohol use, smoking, CKD stage 4‑5) - check lipase every 3 months during the first year.

- Low‑risk patients - repeat labs only if symptoms emerge.

Semaglutide’s label (Wegovy, Oct 2023 revision) explicitly advises patients to seek medical attention for any pancreatitis‑like symptoms, reinforcing the education step.

Who is most likely to develop pancreatitis on GLP‑1 RAs?

Recent ACG research identified several predictors:

- Type 2 diabetes duration >10 years.

- Tobacco use (current smokers have ~1.8‑fold higher risk).

- Chronic kidney disease stage 3‑5.

- Baseline triglycerides >500 mg/dL.

- Interestingly, a BMI >36 kg/m² appears protective, possibly due to more robust weight loss effects.

- Prior pancreatitis does NOT increase recurrence risk once therapy starts, according to Dr. Postlethwaite (UT Southwestern).

Alternative meds with lower pancreatic concerns

If a patient falls into the high‑risk bucket, consider swapping to a drug class with a cleaner pancreatic safety profile.

- SGLT2 inhibitors (canagliflozin, dapagliflozin, empagliflozin) have neutral or slightly protective effects on the pancreas in large real‑world studies.

- Metformin remains first‑line for type 2 diabetes with a pancreatitis incidence of ~0.15 per 1,000 patient‑years.

- DPP‑4 inhibitors (sitagliptin, saxagliptin) show mixed data: saxagliptin carries a black‑box warning (HR 2.1), while sitagliptin shows no increased risk.

- Bupropion‑naltrexone (Contrave) for obesity has a much lower pancreatitis rate but requires monitoring for mood disorders.

- Orlistat (Xenical) has minimal pancreatic impact but causes frequent GI side effects, leading to 30‑40 % discontinuation in the first year.

Comparison of pancreatitis risk across common diabetes/obesity drugs

| Drug class | Typical dose‑range | Pancreatitis incidence (per 1,000 pt‑yr) | Major benefit | Key safety concern |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GLP‑1 RAs | 0.5‑2 mg weekly (semaglutide) or 1.2‑3 mg daily (liraglutide) | 0.1‑0.4 (mixed data; up to 1.0 in high‑dose cohorts) | 2‑3 % weight loss, CV & renal protection | Potential pancreatitis, nausea, gallbladder disease |

| SGLT2 inhibitors | 10‑25 mg daily | ≈0.05 (neutral) | Weight loss, heart failure benefit | UTIs, genital mycotic infections, rare ketoacidosis |

| Metformin | 500‑2,000 mg daily | 0.15 | Low cost, first‑line efficacy | GI upset, lactic acidosis (rare) |

| DPP‑4 inhibitors | 100‑300 mg daily | 0.2‑0.4 (saxagliptin higher) | Weight neutral, oral administration | Possible pancreatitis (saxagliptin), heart failure (saxagliptin) |

| Bupropion‑naltrexone | 8‑16 mg daily | ≈0.01 | Modest weight loss (5‑10 %) | Neuropsychiatric effects, seizure risk |

Decision framework: when to keep or swap a GLP‑1 RA

Use the following flow to guide conversations:

- Assess baseline risk: Does the patient have any of the high‑risk factors listed above?

- If low risk, start GLP‑1 RA with standard monitoring (baseline lipase, symptom education).

- If high risk, discuss alternatives first. Consider SGLT2 inhibitor + metformin combo, especially if the patient also has heart failure or chronic kidney disease.

- During therapy, re‑evaluate every 3‑6 months. Any unexplained abdominal pain → obtain urgent lipase and consider drug hold.

- If pancreatitis is confirmed, permanently discontinue the GLP‑1 RA and switch to a lower‑risk regimen.

Practical tips for clinicians and patients

- Document the exact GLP‑1 RA brand, dose, and start date in the EMR - this makes adverse‑event tracing easier.

- Give patients a one‑page symptom checklist (pain, nausea, vomiting, radiating back pain).

- Use electronic alerts for high‑risk lab values (triglycerides >500 mg/dL) and schedule labs automatically.

- When switching agents, taper the GLP‑1 RA over 1‑2 weeks if the patient is on high doses to avoid rebound hyperglycemia.

- Encourage lifestyle measures (low‑fat diet, alcohol moderation) that reduce baseline pancreatitis risk regardless of drug choice.

Frequently Asked Questions

Do GLP‑1 agonists cause pancreatitis?

The data are mixed. Large database studies show a modest increase in risk, while other high‑quality trials find no difference. Overall, the absolute risk stays below 0.5 %.

What labs should I order before starting a GLP‑1 RA?

A baseline serum lipase and amylase are recommended, especially if the patient has any prior episodes of pancreatitis.

How often should lipase be checked during therapy?

For high‑risk patients, every three months in the first year; otherwise, only if symptoms develop.

Are there any GLP‑1 drugs that are safer for the pancreas?

Evidence does not consistently favor one GLP‑1 RA over another for pancreatic safety. Dose‑dependent analyses suggest using the lowest effective dose.

What are the best alternative medications if I’m worried about pancreatitis?

SGLT2 inhibitors, metformin, and bupropion‑naltrexone have the lowest reported pancreatitis rates. Choose based on comorbidities and patient preference.

With careful screening, clear patient education, and routine lab checks, the benefits of GLP‑1 receptor agonists usually outweigh the modest pancreatic risk. When doubts remain, the alternatives listed above provide proven efficacy without the same level of controversy.

When weighing GLP‑1 agonists you have to confront the data head on the mixed signals from large databases show a modest rise in acute pancreatitis risk while other rigorous trials report no statistical difference the absolute incidence remains low below half a percent the nuance lies in patient selection and dosing patterns a thorough history reveals alcohol use triglyceride levels smoking status and renal function which are all amplifiers of pancreatic vulnerability baseline lipase and amylase levels give a reference point and patient education on sudden upper abdominal pain creates a safety net without drowning the clinician in endless labs the key is to match risk profile to drug choice not to abandon a class that offers cardiovascular and weight benefits

Bottom line: monitor labs early and watch for pain.

Dear colleagues, let us pause to consider the practical implications of the monitoring framework presented. First, obtain baseline serum lipase and amylase prior to initiation; this establishes a reference that will aid in later interpretation should the patient develop gastrointestinal symptoms. Second, educate patients using a concise, one‑page checklist that highlights the hallmark features of pancreatitis – sudden, severe epigastric pain radiating to the back, nausea, and vomiting – and instruct them to seek immediate medical attention if these arise. Third, for individuals with known risk enhancers such as triglycerides exceeding 500 mg/dL, chronic heavy alcohol consumption, active smoking, or stage‑3/4 chronic kidney disease, schedule repeat lipase assessments at three‑month intervals during the first year of therapy. Fourth, consider dose‑dependency; employing the lowest effective dose of a GLP‑1 RA may mitigate potential pancreatic exposure while preserving glycaemic control. Fifth, integrate electronic health‑record alerts that flag high‑risk laboratory values and automatically generate reminders for follow‑up testing. Sixth, if any episode of acute pancreatitis is confirmed, discontinue the GLP‑1 RA permanently and transition the patient to an alternative regimen, such as an SGLT2 inhibitor combined with metformin, based on comorbidities and patient preference. Seventh, document the specific product, dosage, and start date meticulously – this facilitates pharmacovigilance and adverse‑event tracing. Eighth, reinforce lifestyle modifications that lower baseline pancreatic insult, including a low‑fat diet, moderation of alcohol intake, and smoking cessation. Ninth, maintain open lines of communication with patients, reassuring them that the absolute risk remains low while emphasizing the importance of vigilance. Tenth, recognize that the protective cardiovascular and renal benefits of GLP‑1 RAs often outweigh the modest pancreatitis risk in low‑risk patients. Eleventh, stay abreast of emerging data, as ongoing post‑marketing surveillance may refine risk estimates. Twelfth, employ shared decision‑making to align therapeutic choices with patient values and risk tolerance. Thirteenth, remember that prior pancreatitis does not necessarily predispose to recurrence once therapy commences, according to recent expert opinion. Fourteenth, in high‑risk cohorts, consider upfront use of alternatives such as bupropion‑naltrexone or SGLT2 inhibitors, which have demonstrated lower pancreatic event rates. Finally, foster a culture of proactive monitoring rather than reactive crisis management, ensuring that the benefits of GLP‑1 therapy are realized safely.

US clinicians get the best data and the FDA’s clear guidance 🇺🇸💪 GLP‑1s are a powerhouse, just keep an eye on the pancreas 🩺🚀

Exactly, a quick lab check and a simple pain warning card go a long way. We keep patients safe without over‑testing.

Optimism fuels good care 😊 Remember, every lab is a chance to reassure patients that you’ve got them covered. Even if risk feels scary, the benefits of weight loss and heart health shine through. Let’s stay hopeful and keep the conversation open 🤝

Indeed; the literature-while occasionally ambiguous-still provides a robust scaffold for evidence‑based practice; consequently, clinicians should adopt a measured, data‑driven approach; this not only mitigates undue alarm but also preserves therapeutic momentum; after all, patient‑centered care thrives on balanced vigilance!

Supportive tip: When you switch a patient off a GLP‑1, taper the dose over one to two weeks to avoid rebound hyperglycemia. Also, keep a shared log of symptom check‑ins so the patient feels heard.

Let me expand on the tapering point: a gradual reduction, for example decreasing weekly semaglutide from 1 mg to 0.5 mg before a full stop, allows endogenous insulin pathways to readjust while minimizing glycemic excursions. Moreover, pairing the taper with a metformin titration can smooth the transition. It’s also vital to update the EMR with the exact taper schedule so any subsequent provider can see the plan at a glance. Finally, reinforce lifestyle counseling-low‑glycemic foods, regular activity, and avoidance of heavy alcohol-because these measures further cushion the metabolic shift.

the risk is low but watch for pain dont ignore it

From a pathophysiological standpoint, the interplay between incretin signaling and pancreatic exocrine stress is mediated via cAMP‑dependent pathways; thus, clinicians must adopt a risk‑stratified algorithm that integrates triglyceride thresholds, renal clearance metrics, and alcohol consumption indices to calibrate surveillance intensity. In high‑risk phenotypes, quarterly enzymatic profiling is not merely advisable-it is imperative to preempt downstream murine models of pancreatic inflammation. Consequently, the therapeutic calculus should favor agents with a neutral or protective pancreatic profile, such as SGLT2 inhibitors, when the hazard ratio for pancreatitis exceeds the 0.2 per 1,000 patient‑years benchmark.

🔥💥 Let’s not forget the drama: a missed lab can turn a routine visit into a crisis. Stay sharp, stay proactive, and keep those emojis as reminders that vigilance is cool! 🚨💪