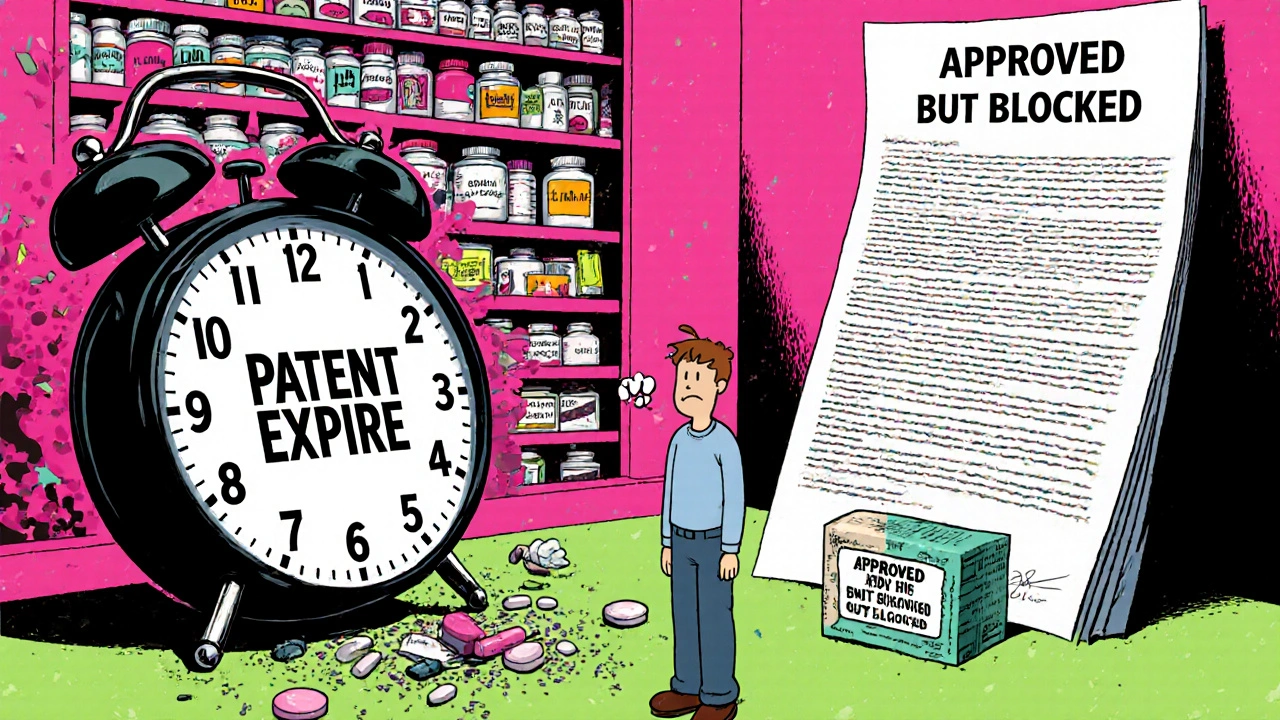

It’s not enough for a brand-name drug’s patent to expire for its generic version to appear on pharmacy shelves. Even when the legal barrier falls, it can take years before patients actually get access to cheaper versions. Why? The gap between patent expiration and market launch isn’t a glitch - it’s built into the system.

The Patent Clock Starts Long Before the Drug Sells

Pharmaceutical patents last 20 years from the date they’re filed. But here’s the catch: that clock starts ticking the moment a company files for a patent - often before the drug even enters human trials. By the time the FDA approves a new drug, 8 to 10 years of that 20-year term are already gone. That leaves only 7 to 12 years of actual market exclusivity. That’s not a flaw in the patent system - it’s how the math works.Regulatory Exclusivity Adds More Layers

Beyond patents, the FDA gives brand-name drugs extra protection called regulatory exclusivity. This isn’t a patent. It’s a legal shield that blocks generics from even applying for approval, regardless of patent status.- New Chemical Entity (NCE) exclusivity: 5 years. No generic can file an application during this time.

- New clinical investigation exclusivity: 3 years. Applies when a drug gets a new use, formulation, or delivery method.

- Orphan Drug Exclusivity: 7 years for drugs treating rare diseases affecting fewer than 200,000 Americans.

- Pediatric exclusivity: Adds 6 months to any existing exclusivity period if the manufacturer studies the drug in children.

The ANDA Pathway Isn’t Quick

Once exclusivity ends, generic makers file an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA). This lets them skip expensive clinical trials. Instead, they prove their version is bioequivalent - meaning it delivers the same amount of active ingredient into the bloodstream at the same rate as the brand-name drug. But that doesn’t mean fast approval. The FDA’s average review time for an ANDA is 25 months and 15 days. For complex generics - like inhalers, injectables, or topical creams - it can take over 3 years. And that’s just the review clock. Before filing, generic companies spend 18 to 36 months developing the product, testing it, and building a manufacturing line that meets FDA standards. That’s not counting the time spent waiting for the brand-name company to release samples for testing - a common tactic used to delay generic entry.Patent Litigation Slows Everything Down

When a generic company files an ANDA, it must check the FDA’s Orange Book - a public list of patents covering the brand drug. If it believes a patent is invalid or won’t be infringed, it files a Paragraph IV certification. That’s a legal challenge. The brand-name company has 45 days to sue. If they do, the FDA can’t approve the generic for 30 months - or until the court rules, whichever comes first. This is called the 30-month stay. But here’s the surprising part: research shows that most generics don’t launch right after the 30 months end. On average, they wait another 3.2 years after the stay expires. Why? Because patent litigation often drags on for years. The average court case takes 37 months just to reach a decision. Even worse, some brand-name companies settle lawsuits with generic makers - but not to speed things up. In a practice called “reverse payment,” the brand pays the generic to delay launch. The FTC estimates these deals cost consumers $3.5 billion a year. In 2021, the Supreme Court ruled these secret deals violate antitrust law - but they still happen.

Patent Thickets Are the Real Bottleneck

One patent isn’t enough. Brand-name companies file dozens. The average drug has 14.2 patents listed in the Orange Book. Some have over 30. These aren’t just for the active ingredient. They cover:- Specific pill coatings

- Manufacturing methods

- Drug delivery systems

- Combination dosing

- Method of use

The First-Mover Advantage - And the Risk

The first generic company to successfully challenge a patent gets 180 days of exclusivity. No other generic can enter during that time. That’s a huge financial incentive. But it’s also a trap. To keep that exclusivity, the first filer must launch within 75 days of FDA approval. Many can’t. Manufacturing issues, quality control failures, or last-minute legal hurdles force them to delay. When they do, they lose the exclusivity - and the profit. In 2022, 22% of first filers forfeited their 180-day window because they couldn’t get their product ready in time.Why Some Generics Never Launch - Even After Approval

The FDA approved 1,165 generic drugs in 2021. But only 62% reached the market within six months of approval. Why the gap? Because approval doesn’t mean availability. If a brand-name company still holds a valid patent, or if the generic maker is stuck in litigation, they can’t legally sell it. Even if the FDA says it’s safe and effective, the law says no. This disconnect is why patients sometimes see a brand-name drug priced at $500 - while the generic version, already approved, sits on a warehouse shelf, legally blocked.Complex Drugs Are the New Frontier

Biologics - drugs made from living cells, like insulin or Humira - are the fastest-growing segment of pharmaceutical spending. But they’re not covered by the Hatch-Waxman Act. Instead, they follow the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA) of 2010. That pathway is slower, more complex, and has fewer legal tools for generics to challenge patents. As a result, generic biologics - called biosimilars - take an average of 4.7 years to launch after the brand’s patent expires. That’s more than triple the time for small-molecule drugs.

Who Controls the Market?

The generic market is shrinking. Three companies - Teva, Viatris, and Sandoz - control 45% of the $70 billion U.S. generic market. That concentration means fewer players are willing to take on risky patent challenges. And when they do, they often focus on high-revenue drugs. A drug making over $1 billion a year faces an average of 17.3 patent challenges. A low-revenue drug? Only 8.2.What’s Changing - And What’s Not

There have been reforms. The CREATES Act of 2019 forces brand-name companies to supply samples to generic makers. The Orange Book Transparency Act of 2020 made patent listings more accurate - cutting disputes by 32%. The FDA’s GDUFA II program aims to cut review times for complex generics from 36 to 24 months. But progress is slow. In Q2 2024, only 62% of complex generic applications met the 24-month target. And patent evergreening is on the rise. A 2024 study found 68% of brand-name drugs get a new patent within 18 months of their original patent expiring - often for tiny changes like a new pill shape or color.Why This Matters to You

Generic drugs make up 92% of all prescriptions filled in the U.S. - but only 16% of total drug spending. They saved the healthcare system $373 billion in 2023. But every month a generic is delayed, patients pay more. A one-year delay on a top-selling drug can cost Medicare $1.2 billion. The median time from patent expiration to generic availability? 18 months. That’s over a year and a half where patients are stuck paying brand prices. For someone on a $500-a-month medication, that’s $6,000 in extra costs - just for waiting.What’s Next?

The FDA is testing AI to speed up bioequivalence testing - potentially cutting development time by 25%. Biosimilars are expected to capture 45% of the biologic market by 2030, saving $150 billion a year. But until patent thickets are broken, litigation is curbed, and regulatory delays shrink, the gap between patent expiration and real access will remain. The system was designed to balance innovation and access. But today, it’s tilted too far toward delay - and patients are paying the price.How long after a patent expires does a generic drug usually become available?

On average, it takes 18 months from patent expiration for a generic drug to become available. But this varies widely - some launch within weeks, while others take over three years due to patent litigation, manufacturing delays, or regulatory hurdles.

Why don’t generic drugs launch immediately after patent expiration?

Even after a patent expires, generic makers must navigate FDA approval, manufacturing setup, and potential lawsuits. Brand-name companies often file lawsuits that trigger a 30-month stay, delaying approval. Many generics also face patent thickets - dozens of overlapping patents - that must be challenged one by one.

What is the Hatch-Waxman Act and how does it affect generics?

The Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984 created the ANDA pathway, letting generic companies prove bioequivalence without repeating clinical trials. It also gave brand-name companies patent extensions and exclusivity periods, while offering first-time generic challengers 180 days of market exclusivity. It was meant to balance innovation and competition - but today, it’s often used to delay generic entry.

What’s the difference between a patent and regulatory exclusivity?

A patent is a legal right granted by the U.S. Patent Office to protect inventions - like a drug’s chemical structure. Regulatory exclusivity is granted by the FDA and blocks generic applications for a set time, regardless of patents. For example, a drug can have 5 years of NCE exclusivity even if its patent expired after 7 years.

Can a generic drug be approved but not sold?

Yes. The FDA can approve a generic drug, but if a brand-name company still holds a valid patent or if the generic maker is involved in active litigation, the generic cannot be legally marketed. Approval doesn’t equal availability - the law still blocks sales until all legal barriers are cleared.

Are biosimilars the same as generic drugs?

No. Generics are exact copies of small-molecule drugs made with chemicals. Biosimilars are highly similar - but not identical - copies of complex biologic drugs made from living cells. They follow a different approval pathway (BPCIA), take longer to develop, and face more patent challenges, which is why they take nearly 5 years to launch on average.

Just had to pay $400 for my blood pressure med last month. My pharmacist said the generic was approved six months ago but still not on shelves. Welcome to American healthcare, folks.

Oh great, another post about how Big Pharma is evil. Let me guess - you think if we just abolished patents, everyone would suddenly get free insulin? Wake up. Innovation doesn’t happen in a vacuum. Someone had to spend $2.6 billion and 12 years to get that drug to market. You want cheaper meds? Then fund R&D, don’t just rage at the people who built the ladder.

Canada has it better. We don’t have this mess. Our generics hit shelves within weeks. Why? Because we don’t let corporations write the rules. You people act like patent thickets are some kind of natural law. Nah. It’s corruption with a white coat. 😤

Wait so the FDA takes 25 months to review a generic? That’s longer than it takes to get a driver’s license in some states. And you’re telling me they can’t just hire more reviewers? This isn’t rocket science. It’s chemistry. And yet somehow we’ve turned it into a 5-season Netflix drama.

My mom’s on a generic for cholesterol. She’s been waiting over a year. I didn’t realize how many layers of red tape were involved. It’s heartbreaking when people skip doses because they can’t afford the brand. We need to fix this.

Y’all are missing the real issue: the 180-day exclusivity window for first filers. It sounds like a reward but it’s actually a bottleneck. Companies sit on approvals waiting for the perfect price point, then delay launch to milk the exclusivity. And if they mess up manufacturing? Poof - exclusivity gone. So they play it safe and drag their feet. It’s not Big Pharma alone - it’s the whole system incentivizing delay.

Of course the generics don’t launch. The Illuminati owns the FDA. The same people who made the brand drug also sit on the review board. You think that’s a coincidence? And the 30-month stay? That’s not a legal tool - it’s a bribery loophole. They call it "patent litigation" but it’s really just corporate extortion with a law degree. 🕵️♂️

My heart goes out to everyone paying $500/month for meds. I just got my generic for $12 after a 14-month wait. 😭 We need to pressure our reps to pass the CREATES Act fully. No more sample withholding. No more patent games. #GenericAccessNow 💪

The entire regulatory architecture is a triumph of legal engineering over public health. The Hatch-Waxman Act, while ostensibly a compromise, functioned as a capitulation to monopolistic interests under the guise of incentivizing innovation. The 180-day exclusivity provision, far from promoting competition, creates a perverse oligopoly wherein the first filer becomes a de facto cartel. This is not market efficiency - it is rent-seeking masquerading as regulatory policy.

Interesting how everyone blames Big Pharma. But who actually files the 30+ patents? The same generic companies that later cry foul when they can’t launch. They’re not victims - they’re players. They game the system too. The real scandal? The FDA’s review backlog is worse than the DMV’s on a Monday. And nobody’s mad at them.

Let’s be honest - this isn’t about access. It’s about control. The entire pharmaceutical industry is a cult of intellectual property worship. You don’t cure diseases - you monetize suffering. And the fact that you’re still surprised by this? That’s the real tragedy. You think a drug is medicine? No. It’s a financial instrument wrapped in a pill. And you’re all complicit.

I’ve been working in generic manufacturing for 18 years. The system is broken, yes - but not because of greed alone. It’s because we’ve never properly funded the infrastructure needed to scale. The FDA needs more inspectors. The labs need better equipment. The supply chains need redundancy. And yes, we need to break patent thickets. But also, we need to stop treating this like a zero-sum game. The goal shouldn’t be to destroy Big Pharma - it should be to build a system where both innovation and access thrive. That’s possible. We just need the will.

Thank you for writing this. I’ve been on a $600/month med for 5 years. I finally got the generic last month. I cried. You’re not alone. Keep fighting.