For decades, bioequivalence studies-the clinical tests that prove a generic drug works just like its brand-name counterpart-were done almost entirely on young, healthy men. It wasn’t because women or older adults didn’t need these medications. It was because the system was built on convenience, not science. But today, that’s changing. Regulatory agencies are finally demanding that bioequivalence studies reflect the real people who take these drugs: women, older adults, and people of all sexes and ages. If you’re developing, reviewing, or even just using generic medications, you need to understand why this shift matters-and what it means for safety, effectiveness, and regulation.

Why Bioequivalence Studies Used to Ignore Sex and Age

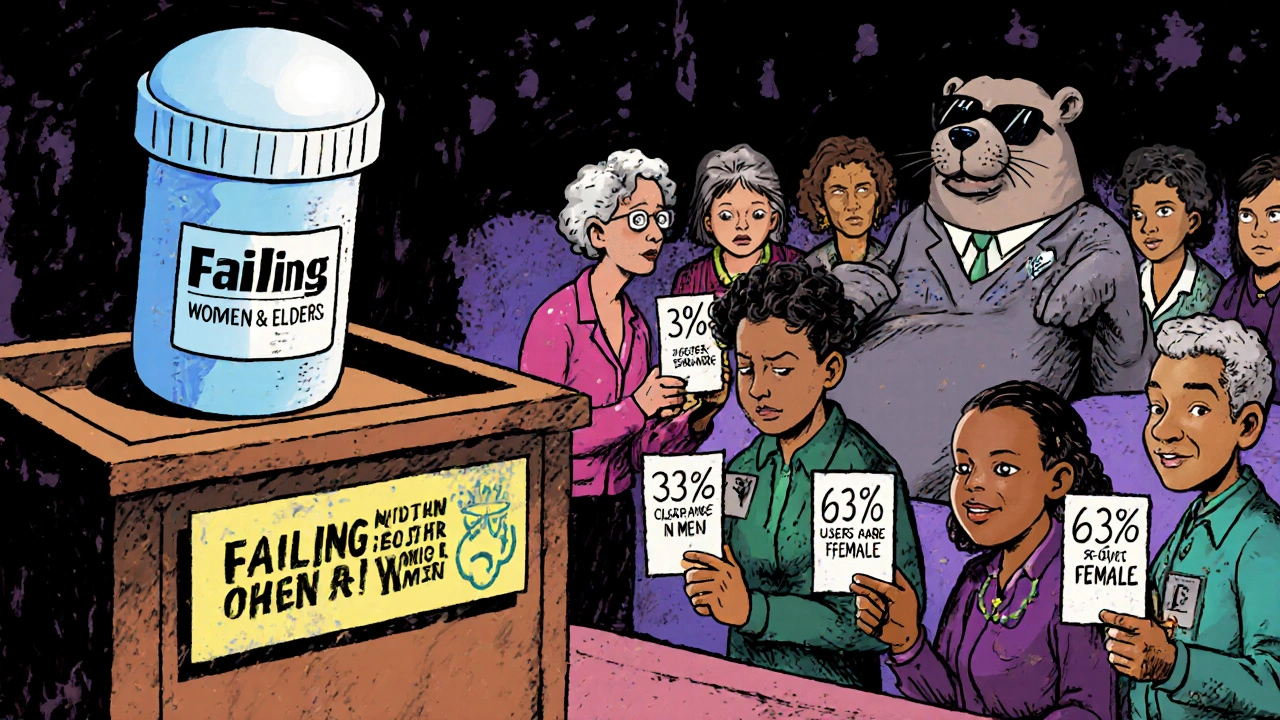

The old model was simple: enroll 12 to 24 young men, give them the brand drug, then the generic, measure blood levels, and call it a day. The logic? Each person acts as their own control. If their body absorbs both versions the same way, the drugs are equivalent. It was efficient. It was cheap. And it was deeply flawed. This approach ignored decades of evidence showing that sex and age affect how drugs are absorbed, distributed, metabolized, and excreted. Women often have different body fat percentages, liver enzyme activity, and kidney function than men. Older adults have slower metabolism, reduced blood flow to organs, and changes in stomach acidity-all of which can change how a drug behaves. Yet, for years, these differences were treated as noise, not data. The result? Generic drugs that passed bioequivalence tests in men sometimes didn’t work as well-or caused more side effects-in women or older patients. Take levothyroxine, a drug used by millions, mostly women. Despite 63% of users being female, most bioequivalence studies for it enrolled fewer than 25% women. That’s not just a gap. It’s a risk.Regulatory Shifts: What the FDA, EMA, and ANVISA Now Require

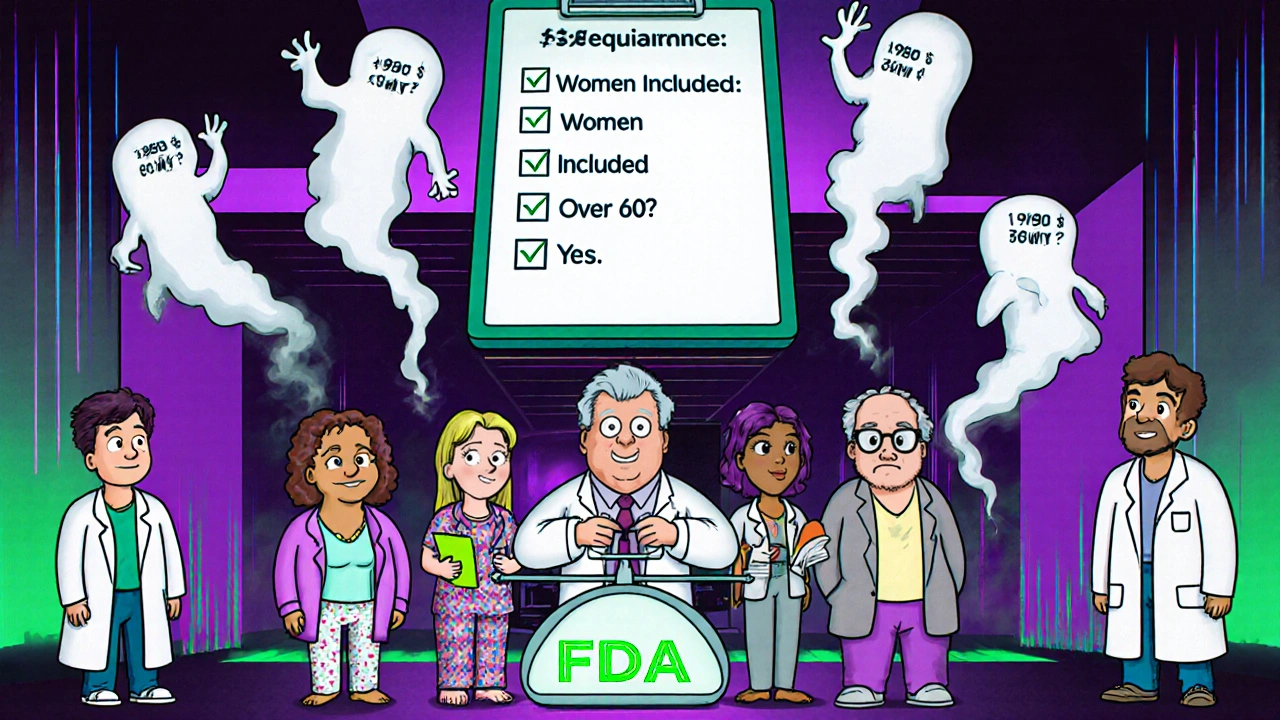

In 2013, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) began pushing for change. By 2023, their draft guidance made it clear: if a drug is meant for both men and women, your bioequivalence study must include both. Not as an afterthought. Not as a token. But in roughly equal numbers-close to a 50:50 split. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) took a slightly different path. Their 2010 guideline says subjects “could belong to either sex,” but doesn’t require balance. That’s changed in practice. While not legally binding, regulators now expect sponsors to justify why they’d enroll only one sex. And if the drug targets older adults? The FDA now requires inclusion of participants aged 60 and up-or a strong scientific reason to exclude them. Brazil’s ANVISA went even further. Their rules demand a strict 18-50 age range, equal male-female distribution, and BMI within 15% of normal. No exceptions. No loopholes. This isn’t just about fairness. It’s about precision. If your study population doesn’t match the real-world users, you can’t trust the results.Why Balance Matters: Real-World Examples

A 2017 study looked at a common cardiovascular drug. In a small group of 14 men, the generic version showed a 79% relative bioavailability compared to the brand-below the 80-125% bioequivalence range. It looked like a failure. But when the same study was repeated with 36 participants-half women-the result flipped. The average was now 98%, well within limits. What happened? In the small male-only group, a few outliers skewed the data. In the larger, balanced group, those extremes canceled out. That’s not a fluke. It’s a pattern. Small studies with unbalanced populations are statistically unreliable. They can falsely flag safe generics as unsafe-or worse, approve ones that won’t work in half the population. Another example: a 2023 University of Toronto study found that 37% of commonly tested drugs are cleared from the body 15-22% faster in men than in women. That doesn’t mean the drug is unsafe. But if your bioequivalence study only tests men, you might miss that women need a slightly different dose to get the same effect. And that’s not theoretical. It’s happened with antidepressants, painkillers, and blood thinners.

Practical Challenges: Why It’s Still Hard to Get It Right

Even with clear guidelines, getting balanced enrollment isn’t easy. Recruitment for women in clinical trials is slower. Many women juggle caregiving, work, or family responsibilities. Clinical trial sites often operate during business hours, making participation harder. Some women are also hesitant to join due to concerns about pregnancy, side effects, or past negative experiences with medical research. Sponsors face 20-30% higher costs when recruiting women. Some try to avoid it by arguing that “the drug is metabolized the same in both sexes.” But that’s a claim that needs proof-not assumption. The FDA now requires written justification for any deviation from balanced enrollment. That means sponsors have to run extra analyses, collect more data, and document everything. And then there’s the statistical issue. Many bioequivalence studies still use small sample sizes-12 to 24 people. That’s enough to detect average differences, but not enough to spot sex- or age-related trends. Experts now recommend 36 or more participants for studies targeting diverse populations. More subjects mean more reliable data. Less chance of false positives or negatives.What Good Study Design Looks Like Today

A modern bioequivalence study that respects age and sex follows a few key rules:- Match the target population. If the drug is used mostly by women over 60, your study should reflect that.

- Enroll men and women in roughly equal numbers. Unless you have strong data showing sex doesn’t affect absorption, aim for 50:50.

- Include older adults. If the drug is for conditions common in aging-like hypertension, diabetes, or osteoporosis-include participants 60+.

- Stratify by sex and age. Randomize participants so each group has the same mix of men, women, young, and older adults.

- Analyze subgroups. Don’t just report the overall result. Look at men vs. women, younger vs. older. If there’s a meaningful difference, it needs to be explained.

- Document everything. Regulatory agencies now demand detailed demographic reports in Clinical Study Reports. Missing data = delayed approval.

The Future: Beyond Sex and Age

This isn’t the end of the story. The next frontier is pharmacogenomics-how genetic differences affect drug response. Ethnicity, body weight, kidney and liver function, even gut microbiome composition are now being studied as factors that could influence bioequivalence. The FDA’s 2023-2027 strategic plan explicitly names “enhancing representation of diverse populations” as a top priority. That includes not just sex and age, but race, ethnicity, and comorbidities. The goal? Generic drugs that work just as well for everyone-not just the people who were easiest to recruit in the 1980s. Meanwhile, researchers are pushing for sex-specific bioequivalence ranges for narrow therapeutic index drugs-medications like warfarin or lithium, where tiny differences in blood levels can cause serious harm. Right now, the same 80-125% range applies to everyone. But if women metabolize a drug slower, should the lower limit be adjusted? That’s the conversation happening now.

What This Means for Patients and Prescribers

You don’t need to run a clinical trial to care about this. If you’re a patient, especially a woman or someone over 60, know that the generic you’re taking may have been tested mostly on men half your age. That doesn’t mean it’s unsafe-but it does mean you should pay attention to how you feel. If your medication seems less effective or causes new side effects after switching to a generic, tell your doctor. It might not be in your head. It might be in the data. For prescribers, this means asking questions: Was the bioequivalence study balanced? Was it done in older adults? Is there evidence this generic works well in women? If the answer is no, consider sticking with the brand-or at least monitor closely.Frequently Asked Questions

Why were bioequivalence studies historically done only on young men?

Early bioequivalence studies used young, healthy men because they were easier to recruit, had fewer confounding health conditions, and were seen as more predictable in how their bodies processed drugs. This approach was based on convenience and outdated assumptions, not science. Regulatory agencies now recognize that this practice led to gaps in safety and effectiveness data for women and older adults.

Does the FDA require equal numbers of men and women in bioequivalence studies?

Yes. According to the FDA’s May 2023 draft guidance, if a drug is intended for use by both sexes, applicants must include similar proportions of males and females in the study-ideally close to a 50:50 split. Deviations require strong scientific justification and documentation.

What age groups should be included in bioequivalence studies?

For most drugs, participants must be 18 or older. If the drug is meant for older adults-like those used for arthritis, heart disease, or thyroid conditions-studies should include participants aged 60 and up. The FDA requires either their inclusion or a detailed justification for exclusion. ANVISA and Health Canada have stricter age limits (18-50 or 18-55), but the FDA’s approach is becoming the global standard.

Are there risks if bioequivalence studies don’t include women or older adults?

Yes. Without representation, you risk approving generics that work poorly-or cause more side effects-in underrepresented groups. For example, women may metabolize certain drugs slower, leading to higher blood levels and increased toxicity. Older adults may have reduced kidney or liver function, altering drug clearance. These differences can go undetected in homogeneous studies, putting real patients at risk.

How can I tell if a generic drug was tested in a diverse population?

The FDA’s Orange Book doesn’t list demographic details, but the Clinical Study Report (CSR) submitted to regulators does. While CSRs aren’t public, you can ask your pharmacist or prescriber if the generic’s bioequivalence study included women and older adults. If the answer is no, consider discussing alternatives with your doctor. Transparency is improving, but it’s still not automatic.

Finally someone gets it. I’ve been switching generics for years and always felt like something was off-especially after 50. Turns out my body wasn’t broken. The study design was.

Thanks for putting this out there.

This isn’t about fairness-it’s about corporate sabotage. The FDA’s ‘guidance’? A PR stunt. Big Pharma still controls the data. They pick the ‘healthy young men’ because they want generics to fail quietly in women and seniors-so they can keep charging $800 for the brand.

And don’t get me started on how they bury the subgroup analyses. I’ve seen the redacted CSRs. This is systemic poisoning disguised as science.

Let’s be real: the 50:50 mandate sounds noble, but it’s a statistical mirage if the sample size stays at 24. You can’t detect sex-based PK differences with n=12 per group. You need at least 36, and even then, you’re gambling with power.

And why are we still using AUC and Cmax as the only metrics? What about Tlag? Or gastric emptying time? Women’s GI motility varies cyclically-yet no one tracks that.

This isn’t progress. It’s performative compliance with a side of ignorance.

USA first. Let the foreigners figure out their own drug math.

Why should we pay more just because some woman in Brazil says so?

Science doesn’t care about identity. It cares about variance.

If sex and age affect pharmacokinetics, then stratification is necessary.

If not, then it’s noise.

But we don’t know until we look.

And we’ve been looking the wrong way for 40 years.

That’s the real tragedy.

This is the moment we’ve been waiting for! The science is here. The data is undeniable. And now-NOW-we have the chance to fix a system that treated half the population like lab rats with bad luck.

Let’s not just update guidelines-let’s rewrite the narrative.

Every woman who’s ever said ‘I don’t feel right on this generic’-you were right.

And now the system has to listen.

This isn’t change. This is justice.

Wait so now we need 50 50 but in india we have like 80% men in trials because women dont come to hospitals? This is american logic. Not global. Also why not include poor people? They dont take generics they take knockoffs from street vendors. So why care about sex if the drug is fake anyway?

My grandma switched to a generic levothyroxine and started feeling like a zombie. She went back to the brand. Problem solved.

Turns out the study was done on 20-year-old guys.

So yeah. Don’t trust the label.

Trust your body.

Valid point. This shift is long overdue. But we need to be careful-adding diversity without proper power analysis creates false negatives. We’re not just checking boxes. We’re building better science.

Let’s fund the research. Train recruiters. Make trials flexible.

And above all-listen to patients. They’re the real endpoints.